a toast to: andré françois

"Sometimes there is a painting that’s not finished and one sleeps on it, then looks at it in the morning and it finished by itself.”

I spent the past couple of days hemming and hawing over what I would focus on in this Sunday’s post when, as if by magic, I received a package from Enchanted Lion Books containing the answer. Inside, I found a requested copy of their latest release, Lamberto, Lamberto, Lamberto (more on that soon!), and, to my delightful surprise, a selection of three books by André François. If you recall, I briefly wrote about François in a previous post, sharing some of his magnificent illustrations in The Adventures of Ulysses (1960). That was my introduction to François, and I’ve been eager to explore more of his work ever since.

An influential graphic designer, cartoonist, and illustrator, André Farkas (later François) was born in 1915 in Timisoara, Romania, (then called Temesvar, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire). According to his obituary in The Times, he recalled Timisora as,

a fair-sized town with two cinemas and colour-coded trams for the benefit of those who could not read the route number or destination. He looked forward to the arrival of the circus with special excitement because one of his father’s 12 brothers, Armand, had run off to join the circus when he was 14. He worked as a sword eater and juggler, and eventually married into the Salomonskis, one of the great Russian circus families. This story stimulated André’s imagination, and circus motifs would later figure among his favourite themes — as did animals, in which he took a close interest during summer holidays on an uncle’s farm in Romania.

In 1934, he moved to Paris, and by the late 1930s, had become a French citizen, “adopted an unobtrusively French name and was finding work as a freelance cartoonist for Parisian newspapers and magazines.” He met and married an Englishwoman, Margaret Edmunds (who later changed her first name to “Marguérite”) and had two children. Hiding from the Germans in occupied Paris, they obtained false papers and moved their family to Haute-Savoie—a region in the Alps of eastern France, bordering Switzerland and Italy.

After the war ended, in 1945 the family settled in Grisy-les-Plâtres, a small village north of Paris, where François remained until his death in 2005. François adorned the walls of the modest farmhouse with a series of “trompe l’oeil” paintings (a French phrase translating to “trick the eye”)—masterful illusions that reflected his artistic ingenuity and playful spirit.

In December 2002, a fire destroyed his studio and nearly all of its contents. Just before the fire, photographer Sarah Moon created a short film (embedded below) of François working in his atelier, preserving a quirky and intimate record of his creative process. In the film, François discusses his recurring subjects: pebbles, the sea, mermaids, women—and birds. On the subject of birds, François said, “Birds… there is nothing closer, nothing further away from us. They often frighten me. And in fact, I could easily have a tamed ostrich in the atelier, but not a tiny bird flying all around me, that makes me…that scares me much more.”

In the six months following the fire, François created more than 60 new pieces using the ashes and charred remnants of his earlier work as materials.

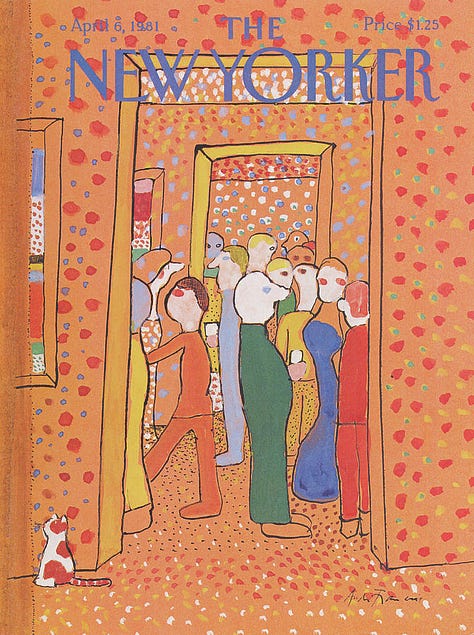

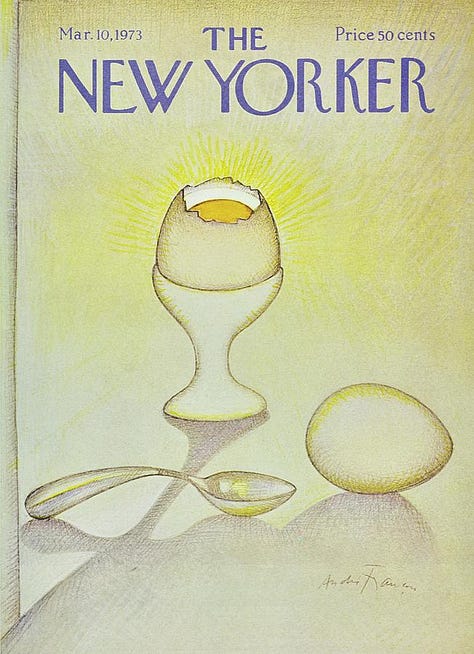

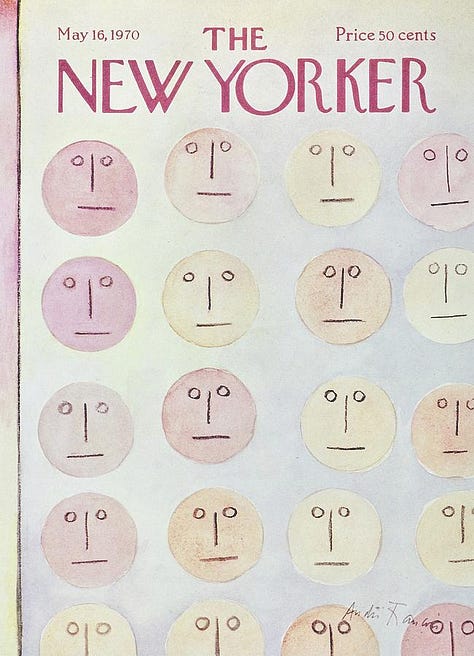

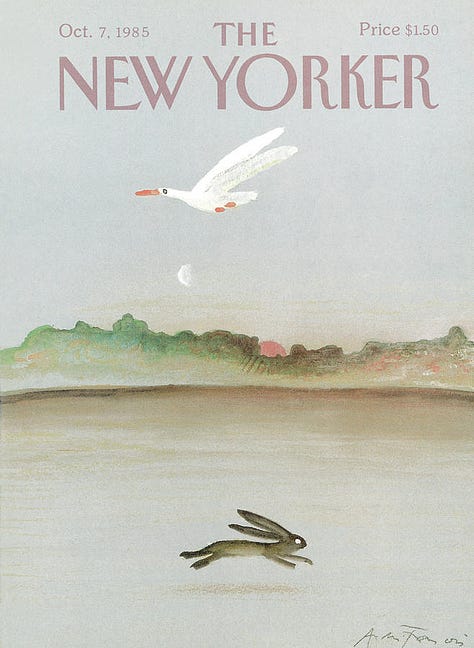

I would be remiss to exclude the fact that from 1963 to 1991, François illustrated 56 covers for The New Yorker. Here is a selection of some of my favorites:

François left an indelible mark on children's literature—a fact that cannot be overstated in a newsletter dedicated to the very subject. Enchanted Lion’s reissuing of three of his books, originally published between 1949 and 1958, speaks to their enduring relevance and timeless charm, which continues to captivate new generations of readers.

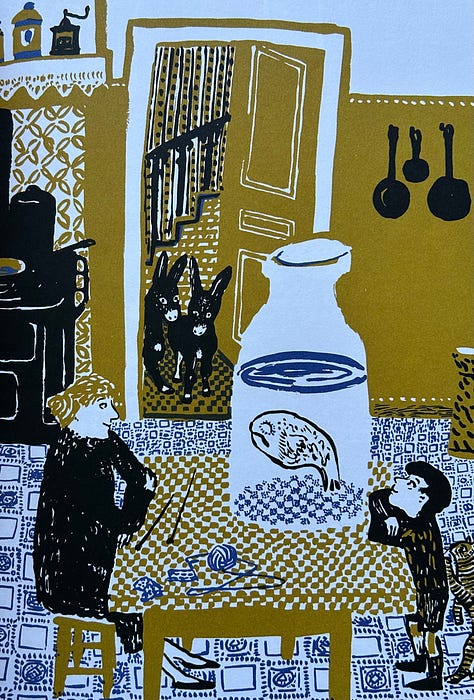

Little Boy Brown by Isobel Harris and André François (1949)

Little Boy Brown marks François’s first foray into children’s illustration. The story follows a four-and-a-half-year-old boy who lives in a hotel in “the City,” one which features tunnels that go all the way to the subway and to the buildings in which his parents work—no venturing outside required. Unlike his parents, the little boy loves fresh air and relies on his chambermaid, Hilda, to take him on daily outdoor jaunts. The boy is invited to spend a day in the country at Hilda’s family home. His new surroundings are at once unfamiliar and comforting: people who keep their front door unlocked, houses sans elevators (Stairs! Which you can run up and down multiple times!), chaotic cake-baking, pets roaming freely, impromptu snowman building. Maria Popova writes of the book,

The story itself, at once a romantic time-capsule of a bygone New York and a timeless meditation on what it’s like to feel so lonesome in a crowd of millions, invites us to explore the tender intersection of loneliness and loveliness…Underpinning the charming tale of innocence and children’s inborn benevolence is a heart-warming message about connection across the lines of social class and bridging the gaps of privilege with simple human kindness.

François's illustrations exude effortless mastery, revealing new details with every reread and making the expansive pages even more rewarding. I'm thrilled this book is back in the world!

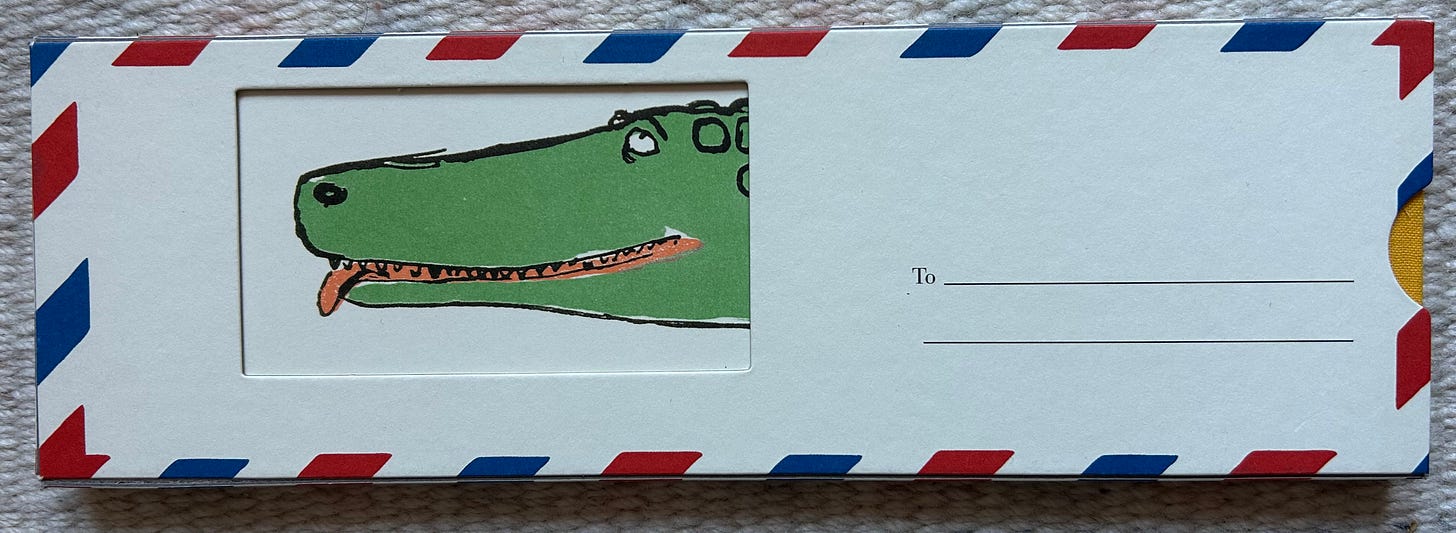

Crocodile Tears by André François (1956)

As an object, this book is a wonder. A mysterious parcel containing a silly looking crocodile with his tongue out? Count me in! Its pages reveal the secrets of catching a crocodile (spoiler: a trip to Egypt is essential), transporting said crocodile (hint: the book’s sleeve just happens to be the perfect fit.), and the realities of cohabitation (expect the crocodile to steal the show at every dinner party). If a child has ever questioned an idiom you’ve never given a second thought, this book is for you. François’s story is a delightful ode to children’s innate curiosity—and the adults they turn to for answers.

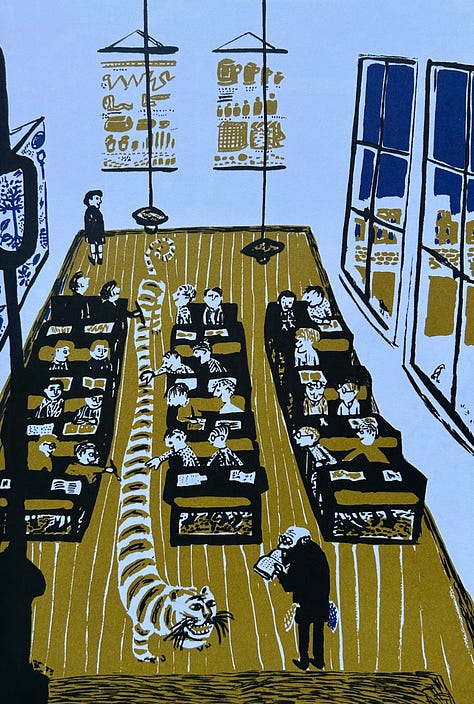

3. Roland by Nelly Stéphane and André François (1958)

À la Harold and the Purple Crayon, our titular character, Roland, can think, draw, or touch something, utter the word ‘crack,’ and bring it to life. A tiger interrupting a class, a snowy scene so treacherous school is cancelled, a fur coat transforming into a flurry of little fur animals—these are just some of the fruits of Roland’s imagination. Roland is perhaps the greatest testament to François’s genius; like the eponymous boy, he conjures rich, full worlds with just a few colors, broad brushstrokes, and boundless creativity.

If this was your introduction to André François, I hope you found this post as enjoyable to read as it was to write. And if you’re already familiar with his work, I hope it inspires you to dust off your copy or revisit his oeuvre with fresh eyes.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy children’s books and reading about them, and want to help keep this newsletter free for everyone, consider subscribing for just $5/month. No offspring required.

You have the makings of a children's book editor my girl. Love these posts. Thx.